Four years ago, a casual hallway conversation between Virginia Tech “work buddies” Brian Huddleston and Heather Parrish led them to embark on a life-transforming journey.

According to Huddleston, a support technician on the IT team at the Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine, “Heather and I were work friends. We didn’t go to each other’s houses or know each other’s families. We talked when we saw each other, but that was about it. I think I once bought her a bag of chips from the vending machine.”

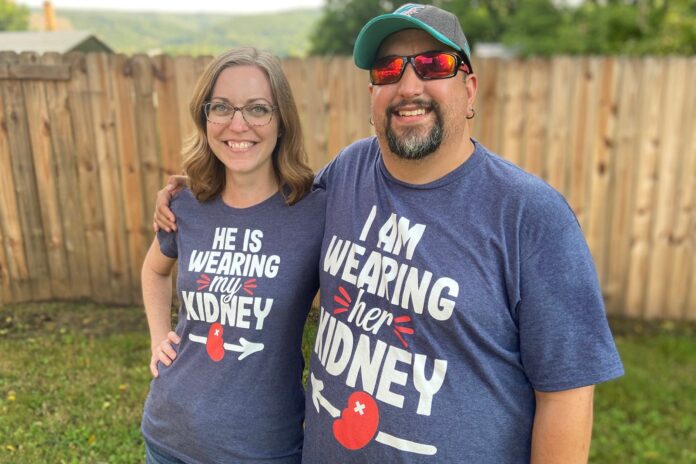

In exchange, Parrish, formerly an administrative assistant at the veterinary college who now works at the Institute for Policy and Governance in the College of Architecture and Urban Studies, gave Huddleston one of her kidneys — hardly an even trade by any stretch of the imagination.

“I remember Brian once mentioning that he had a genetic kidney disorder,” said Parrish, who was concerned about her colleague at the time. Huddleston, however, assured her that the disease seemed to be under control.

Doctors had first noticed a problem with Huddleston’s kidney function when he was a teenager, but for years, he was able to lead a normal life. The situation took a more serious turn four years ago when a routine checkup revealed worrying changes in Huddleston’s kidney function. He altered his diet; and once again, the disease was brought to heel.

“I was able to manage things for a long time by being careful,” Huddleston said. Despite his best efforts, a bout of Henoch-Schonlein purpura, or HSP, a relatively common illness that typically affects children, sidelined him in early 2019. In most people, HSP resolves on its own after a few weeks, but because of Huddleston’s already-compromised kidney function, the disease sent his body into a tailspin.

Kidneys filter out waste and release compounds that regulate the body’s bone health, blood pressure, and creation of red blood cells — essential functions. Huddleston’s kidneys had lost these crucial filtering abilities.

“At that point, my kidneys were just useless bags of fluid,” Huddleston said with characteristic wry humor. “I was admitted to the hospital, and I started hemodialysis. Even after I was discharged, I had to spend three days a week hooked up to a machine just to stay alive.”

The average life expectancy of a person on dialysis is about 10 years. Without a new kidney, the 41-year-old husband might not outlive his eight beloved rescue dogs and cats.

During his illness, Huddleston continued sharing updates on his Facebook page. By then, Parrish had left her job at the veterinary college, but she still stayed in touch with former colleagues through social media.

“I saw people posting things on Brian’s page like ‘Let me know if there’s anything I can do to help,’ and I thought, ‘There is something I can do.’” If Huddleston were going to survive, he didn’t need cheery get-well cards or flowers: He needed a new kidney.

Through online research, Parrish discovered that, typically, more than 110,000 men, women, and children are on the national transplant waiting list and that more than 80 percent of those people are waiting for a new kidney. It was a long line, much too long for her liking.

Parrish reached out to the transplantation team at the University of Virginia (UVA) and began the arduous process of match testing. The early signs were good. Parrish and Huddleston shared a blood type and had compatible antibodies. Further testing revealed that Parrish’s kidneys were in tip-top shape.

It was comforting to Parrish to know that even if she and Huddleston weren’t a match, her donation could start a “donor chain” allowing her kidney to be matched with someone else while another kidney could then be made available for Huddleston.

Working with Virginia Tech’s Human Resources, Parrish arranged for paid leave under the Bone Marrow/Organ Donor policy that provides time off to eligible employees donating bone marrow or an organ; in any calendar year, the policy also includes recuperation for up to 30 days. This additional leave, along with solid support from her boss, her co-workers, and her family, eased the way for surgery to be scheduled in March 2020.

Donors and their families do not pay for medical expenses associated with organ and tissue donation. And while much of Huddleston’s care was covered by insurance, expenses such as ongoing visits to UVA and a hotel stay for his wife when he was hospitalized in Charlottesville were not.

The staff association at the veterinary college stepped in to help. “This is just what we do,” said Tami Quesenberry, a licensed veterinary technician who co-chaired a massive fundraising effort, including a goods and services auction that raised nearly $10,000 for Huddleston. The situation “brought members of this great big veterinary family together like never before,” she said.

Once the COVID-19 pandemic began to take hold, the original surgery date had to be postponed because of the many unknowns. Although it was a disappointing blow after months of careful preparation, Huddleston and Parrish persisted, and the pandemic became a mere footnote to their eventful couple of months. As Parrish recounted that story recently, Huddleston chimed in, “Oh, yeah, and then there was the coronavirus.”

The team at UVA quickly adapted, however, and the surgery was scheduled for May 14. As expected, the pandemic restrictions made an already-stressful event even more stressful. Parrish’s and Huddleston’s spouses were not allowed entry into the hospital and had to drop off both donor and recipient outside the hospital door and were allowed to see them only briefly as they recovered.

Still, their recoveries went smoothly, and both are doing well today. Parrish’s kidney, which the two nicknamed “Aunt Lydia,” has settled into her new home. “Aunt Lydia and I are good.” Huddleston said with a laugh. “I didn’t realize how sick I’d been until I felt well.”

For her part, Parrish is nonchalant about the magnitude of her gift. “For me, this was a no-brainer,” she said. “I had two healthy kidneys. Brian didn’t have any. I knew he needed help, and I was in a position to help.”

Although Huddleston, his friends, and his family will disagree, Parrish insists that she’s not extraordinary. She encourages anyone who wants to talk about the possibility of becoming a living donor to reach out to her. “Anyone can do this,” she said. “That’s what I want the people who hear our story to know: They can do this, too.”

In the coming months, Parrish and Huddleston are planning to participate in a virtual National Kidney Walk event on Oct. 17. As part of the 2020 Southwest Virginia Walk, they hope folks will join their team, the Teenie Beanies. A joke between Parrish and Huddleston, the name was created because Huddleston’s nephrologist said that Parrish has small kidneys.

For more information about becoming a living donor, contact the National Kidney Foundation.

— Written by Mindy Quigley, clinical trials coordinator in the veterinary college’s Department of Small Animal Clinical Sciences