State and federal officials are concerned Virginia will not meet its 2025 overall commitment to reduce polluted runoff into the Chesapeake Bay; 90% of which must come from the agriculture industry, according to environmental advocates. However, farmers and landowners can access a record $235 million next year in state funds to help pay for an array of practices aimed at protecting the nation’s largest estuary. The funding is available through the Virginia Agricultural Best Management Practices Cost-Share Program.

State and federal officials are concerned Virginia will not meet its 2025 overall commitment to reduce polluted runoff into the Chesapeake Bay; 90% of which must come from the agriculture industry, according to environmental advocates.

However, farmers and landowners can access a record $235 million next year in state funds to help pay for an array of practices aimed at protecting the nation’s largest estuary. The funding is available through the Virginia Agricultural Best Management Practices Cost-Share Program.

Progress in wastewater treatment plants are the main reason why Virginia is on track to meet its overall 2025 deadline, but more work needs to be done to address pollution runoff from agriculture, as well as suburban and urban areas, show reports from the Chesapeake Bay Foundation and Environmental Protection Agency.

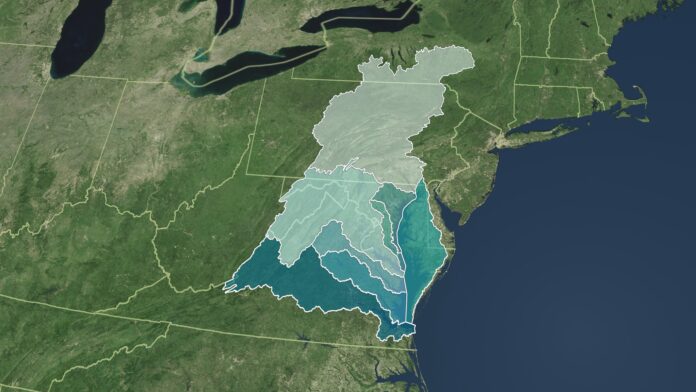

The Chesapeake Bay Executive Council, which guides the policy agenda and conservation and restoration goals for the Chesapeake Bay Program, met Tuesday with state leaders in the Chesapeake Bay watershed to discuss reevaluating the 2025 deadline.

Gov. Glenn Youngkin said during the meeting that it was a “difficult recognition” when he took office in January that Virginia was not on track to meet its 2025 goals.

“I think we have a clear commitment to meet those goals,” Youngkin said. “It’s not a matter of hitting them, it’s a matter of when.”

Agriculture is Virginia’s largest industry by far and is the most significant source of nutrient and sediment pollution in the Chesapeake Bay, according to the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality and the Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services.

Cattle can erode stream banks, causing runoff from fertilizer and sediment to flow into waterways, said Peggy Sanner, Virginia executive director for the Chesapeake Bay Foundation. Cattle waste further reduces water quality, and can lead to algae blooms which are harmful towards aquatic life, Sanner said.

The cost-share program has its roots from back in the Great Depression era, Sanner said. People began to understand the need to improve farm practices to increase productivity, but also to protect the soil so that it wouldn’t wash off in times of rain.

The program’s funding has nearly quadrupled since 2020, according to the Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation, or DCR.

Nearly 23,000 participants have enrolled in the cost-share program since 1998, according to the DCR. There are approximately 54,000 farmers in Virginia.

Bobby Whitescarver and his wife Jeanne Hoffman enrolled in the program in 2020, after buying a farm in Augusta County. They received thousands of dollars from the state after projects were installed through a contract with the Headwaters Soil and Water Conservation District to improve the water quality around the 100-acre plus farm.

Approximately a mile of fencing along streams was installed to keep cattle out of the water, along with internal fencing for rotational grazing. Around a mile of new underground pipeline delivers water to six cattle watering stations. Native hardwood trees were also planted along the streams to create a forest buffer, which helps absorb runoff containing pollutants from fertilizer, and other sources, from entering the water.

Whitescarver was reimbursed 100% of the costs of installing the practices within a month of completion, he said, and received incentive payments for the acreage along the streams that were fenced off from the cows. The payments are given to farmers to install certain practices under the promise they will be maintained for a certain number of years outlined in their contracts.

“The process was incredibly streamlined,” Whitescarver said. “We were really pleased with how everything worked.”

Farmers can get partial or full funding for installing best management practices such as rotational grazing, wetlands preservation and planting cover crops. There are more than 70 practices offered through the program.

“It’s a program by which the state basically pays farmers to help them do the practices that achieve both of those goals of conservation of soil and water, while helping the farmers economically,” Sanner said.

The state Water Quality Improvement Fund received $313 million from last year’s surplus, much of which was allocated to the program overseen by the DCR.

The increased public awareness of the record funding increases means there’s also an increased awareness of the needs for the best management practices, DCR stated in an email.

Reception of the program has been very positive, DCR stated. Many districts are reporting that they are seeing record levels of participation this year.

A farmer can be reimbursed up to $300,000 per year for implementing the practices. State income tax credits are also available to farmers for the purchase and use of certain conservation equipment for installing practices specified by local soil and water districts.

“Farmers want clean water, they want to produce a safe product,” said Martha Moore, senior vice president of governmental relations for the Virginia Farm Bureau Federation.

Conservation practices help farmers save money because less fertilizer and soil is wasted through runoff, according to the DCR. When farmers can provide cleaner water sources through watering stations, livestock are better protected from possible injuries that occur from streams and rivers, according to DCR. Overall herd health is also improved.

“Cost-share pays financially now — but the practices can also benefit farms for years to come,” DCR stated.

A farmer or landowner interested in taking part in the program can contact their local soil and conservation district to start the process.

The program is “the best tool that helps farmers help themselves and help the environment at the same time,” Sanner said.

By Meghan McIntyre / Capital News Service