Lucy, with her boundless puppy-like energy even at 12 years old, is more than just a pet to Susan Ketcham. She’s now part of a research project that could transform the way we treat brain cancer – in both dogs and humans.

This study at Virginia Tech’s Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine explores an innovative therapy called histotripsy. It’s a leap forward from traditional cancer treatments, harnessing the power of focused ultrasound to break down tumors with precision.

When Lucy began experiencing seizures last July, Ketcham, a clinical nurse specialist, knew something more serious was the cause. The diagnosis of a brain tumor was devastating, but Ketcham was determined to explore all treatment options available. She discovered the histotripsy trial during her search and quickly reached out.

“Being in human medicine myself,” said Ketcham. “I work in operating rooms and am very familiar with focused ultrasound, so I was eager to learn more.”

Collaborative mission, translational impact

The trial is led by John Rossmeisl, the Dr. and Mrs. Dorsey Taylor Mahin Professor of Neurology and Neurosurgery, and Rell Parker, an iTHRIV scholar and assistant professor of neurology and neurosurgery.

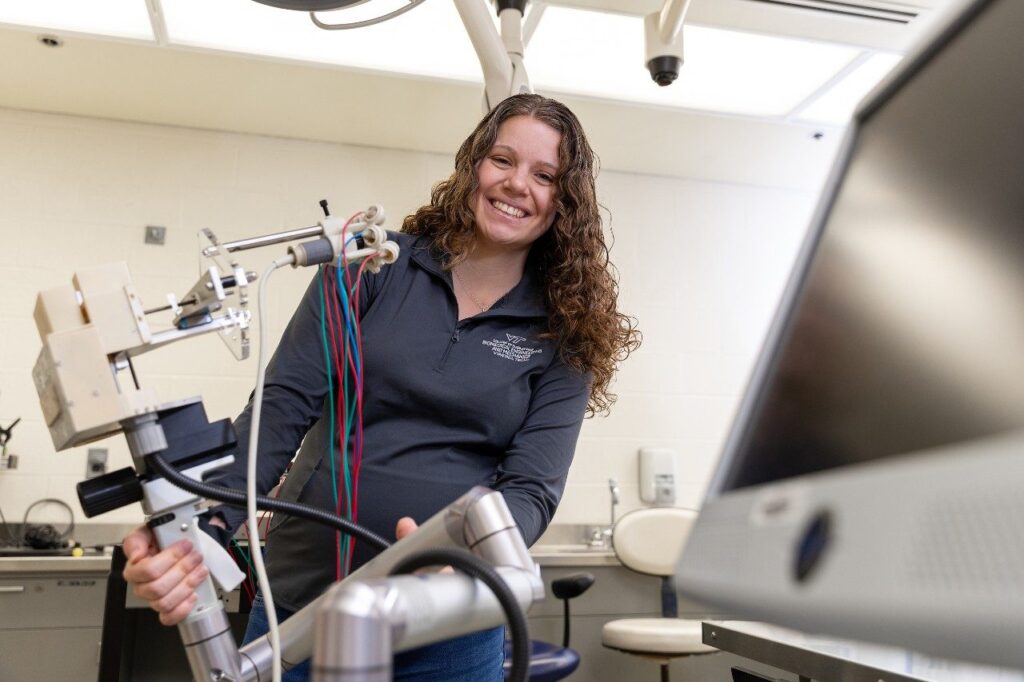

Also on the team is Lauren Ruger, a postdoctoral associate in Eli Vlaisavljevich’s lab in the Department of Biomedical Engineering and Mechanics where histotripsy is extensively researched. She’s adapting the equipment used in the study to make it safe and effective for their canine patients.

“I had wanted to be a veterinarian when I was younger before deciding to become an engineer,” said Ruger. “So I love having the opportunity to use my skills as an engineer to influence animal health.”

This trial offers an essential stepping stone in developing less invasive treatment options for brain cancer and is supported by the Focused Ultrasound Foundation and the Canine Health Foundation, highlighting the widespread commitment to results across species.

Hope for histotripsy

“Histotripsy uses acoustic energy, or sound waves, to modify tissue,” said Rossmeisl. “The intent is to cause a mechanical disruption of the tissue – killing cancer cells.”

The technology was developed by researchers at the University of Michigan in the early 2000s.

The advantage is precision. Unlike traditional surgery, histotripsy can focus its impact on the tumor itself. “We could potentially treat these hard-to-reach brain tumors we normally can’t access with traditional surgery,” said Parker.

“We really don’t have great ways to treat brain cancers in patients,” said Rossmeisl. “Even when you do surgery, radiation, or chemotherapy alone or in combination, usually, you’re not creating a cure.”

However, there is hope that histotripsy could be used to activate the body’s immune response and have it attack cancer cells, called the abscopal effect. Clinicians also see fewer side effects compared to other traditional treatment options.

About the procedure

The study currently still involves surgery to access brain tumors, which is the gold standard of care for this type of diagnosis. This allows for direct targeting of the tumor with the histotripsy transducer, delivering focused sound waves for precise treatment.

“When we do the surgery, we can see the tumor via ultrasound,” Parker said. “We can see that we’re treating the appropriate cells, and then we also do an MRI to ensure that we’ve targeted the right area.”

After the histotripsy treatment, surgeons carefully remove the treated tumor. This tissue provides crucial insights into the technique’s effect on cancer cells, helping researchers refine the technology for future applications.

“It gives us the advantage of being able to look at the tissue that’s been broken down to ensure that we’re getting the desired effect from the histotripsy therapy,” said Ruger.

While the science is complex, the stories of patients like Lucy are reminders of why this work matters. “The recovery was quick, the incision was small,” Ketcham said. “She’s back to her playful self, and knowing she’s helped advance science and technology is amazing.”

Parker added: “We’re happy to say that the procedure has been safe for our patients, and we’ve been able to treat them appropriately.”

Looking toward the future of treatment

A long-term goal of this study is to develop a completely non-invasive treatment that would eliminate the need for surgery. The team is in the early stages of exploring this possibility, citing several challenges to realizing a solution that could be widely available.

“Transmitting ultrasound through the bones of the skull is very difficult,” said Ruger. “And then accurately focusing it in only the areas you want to treat with histotripsy adds another layer of complexity.”

However, the technique can be successfully applied through the skin, explained Rossmeisl. “That would be a paradigm changer. We would make surgically treating tumors a lot more widely available.”

“Even though I love neurosurgery,” he added. “Anytime I can do something that doesn’t require putting the patient through a complex and invasive procedure and get them home quicker, that’s always a good thing.”

To learn more about eligibility criteria or enroll your dog in the trial, please contact John Rossmeisl at [email protected] or 540-231-4621 or Mindy Quigley, clinical trials coordinator at [email protected] or 540-231-1363.