by Gene Marrano

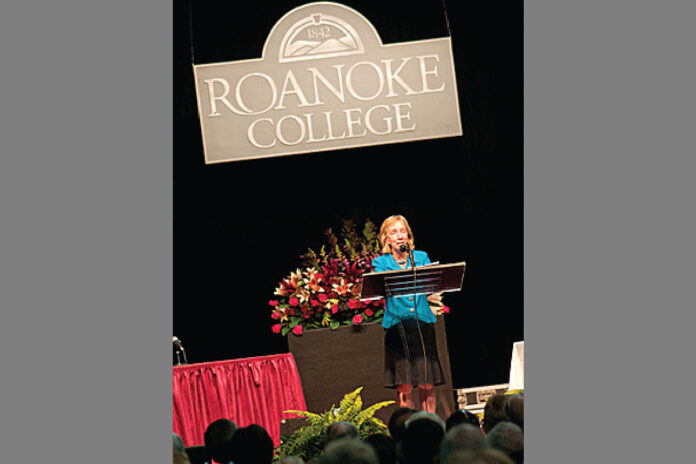

Simply put, Doris Kearns Goodwin is a “rock star” – as evidenced by the several thousand people who jammed the Bast Center at Roanoke College to listen to the noted historian and author last week. Goodwin – also known for being an avid Boston Red Sox baseball fan – delivered a lecture entitled “Presidential Power After Lincoln” on Constitution Day. That was apropos, since Goodwin wrote “Team of Rivals,” about the Abraham Lincoln presidency, focusing on the fact that after he was elected in 1860, the 16th president brought his three closest rivals for the Republican nomination into the White House cabinet. Steven Spielberg is making “Team of Rivals into a movie.”

Goodwin appeared as part of Roanoke College’s Henry H. Fowler Program for 2011-2012, a series of lectures that will be held on campus. The theme for this year’s program is Mystic Chords of Memory: Results of the Civil War. “Mystic Chords” is a phrase used by Lincoln in a speech. Roanoke College president Mike Maxey noted before Goodwin was introduced that Roanoke College was one of the few institutions of higher learning that operated during the Civil War, with the campus used as a field hospital at one point. “That war changed what America has become,” said Maxey.

Roanoke College dean and vice president Richard Smith remarked on Constitution Day that it “was only 150 years ago that the Constitution was called into question [during secession].” He then introduced Goodwin, saying, “no one is better to lead us in a conversation [about Lincoln and presidential power].”

Goodwin, a New Yorker who now lives in Boston (her baseball allegiance changed from the departed Brooklyn Dodgers to the Red Sox along the way) earned a PhD from Harvard, where she also taught. Goodwin, then Doris Kearns, was also an intern in the White House during the Lyndon Johnson administration, where the “minor league womanizer” as Goodwin put it, liked to dance with the 24-year-old future author at White House functions.

Johnson, a champion of civil rights after the Kennedy assassination, was “roundly defeated by the war in Vietnam,” said Goodwin. Henry Fowler, for whom the Roanoke College lecture series is named, was a Treasury Secretary under LBJ.

She spoke of the “uneasy compromise” forged by the founding fathers, who envisoned a strong central figure as president, with a system of checks and balances developed through the Congress and Supreme Court.

Lincoln thought the Civil War would be a short affair, noted Goodwin, who said her favorite president “stretched the Constitution” by suspending Habeas Corpus during the war. Lincoln justified emancipation of the slaves and military action by explaining that they were “providing invaluable aid to the confederacy” in the early days of the War Between the States.

She marveled at how Lincoln overcame a lack of formal schooling, and his way with words. As a young man Lincoln wanted to do something that would leave his mark on the world. “That ambition became his lodestar,” said Goodwin. Lincoln overcame severe depression in his 30s—friends and family removed all sharp objects from his room at one point – and several election defeats before he eventually won the presidency.

The subject of another Goodwin book, Franklin Roosevelt, was the result of six years of research. FDR was “far more successful … in keeping the Constitution sacred” during wartime. Still, Roosevelt bypassed Congress before America got involved in World War II in order to sell Britain 50 old destroyers its navy needed to hold off the Nazis.

Goodwin recalled that Winston Churchill would come to the White House and stay for weeks during FDR’s tenure. On an overnight visit there – invited by Bill and Hillary Clinton – she roamed the halls at night with the Presidential couple and her husband Dick, trying to figure out where Churchill slept and took his famous baths, with cigar in tow.

Her husband worked for the Kennedy administration, and even dated Jacqueline Kennedy for a while after the President was killed in Dallas. Goodwin said Mrs. Kennedy would later call Dick just to say hello in “that throaty voice,” after the Goodwins were married.

Goodwin marveled at the public-private partnership that helped supply the war machine during WWII, and lamented about the Tonkin Gulf resolution in Congress that gave Lyndon Johnson carte blanche to prosecute the Vietnam War. “It turned out to be his Achilles heel,” she noted.

The proliferation of media outlets today has diminished the bully pulpits presidents once had, according to Goodwin, making it harder for them to push agendas through. But she praises programs like The Daily Show with Jon Stewart and the Colbert Report, for bringing the issues to young people in formats they can appreciate. She’s also been a guest on both shows several times.

Today, members of Congress on both sides of the aisle aren’t collegial, or even friends, as was once the case, making compromise harder. “If the right, strong leader came along it still might be possible,” said Goodwin, who said that Barack Obama, when asked about him during a Q&A segment, “[has] to lead … [has] to make a decision.”

Consensus isn’t always possible – that’s what she thinks Lincoln would tell Obama, who called Goodwin to discuss “Team of Rivals” when he ran in 2008. A leader, says Goodwin, “has to decide what they want. A leader has to take the lead.”

“I have loved history for as long as I can remember,” said Goodwin, who whetted her appetite for storytelling by keeping a scorecard during Dodgers games she listened to on the radio while growing up on Long Island. Then she would recount games in great detail for her father when he got home from work.

Now, said Goodwin, evoking laughter, she’s been “living with dead presidents” for most of her career. Next up, a book on Theodore Roosevelt is in the works.

The next lecture in the series, “Lincoln and Race” takes place on Nov. 6. See Roanoke.edu for details.