Do you know what style of beer you like? Wine? Do you know what type of hard cider you prefer? If you’re like most Americans, you could probably answer the first two questions with confident specificity, but the last one might give you pause.

Despite having spent most of the last decade in a period of rapid expansion, the U.S. hard cider market’s growth has begun to slow. Recent years have seen an abundance of small craft cideries spring up, injecting innovation and variety into the market and ensuring that consumers have more choice than ever before in what type of cider they drink.

But the resulting sudden abundance of options presents a problem. American hard cider has grown so quickly as an industry that a unified descriptory language never developed for it. Consumers don’t know what to look for when buying cider, and cider-makers aren’t consistent in what they put on their bottles to represent the flavors inside, leading to a branding identity crisis for the beverage.

A pair of researchers from Virginia Tech’s Department of Food Science and Technology and Cornell’s Department of Population Medicine and Diagnostic Sciences are teaming up to change that.

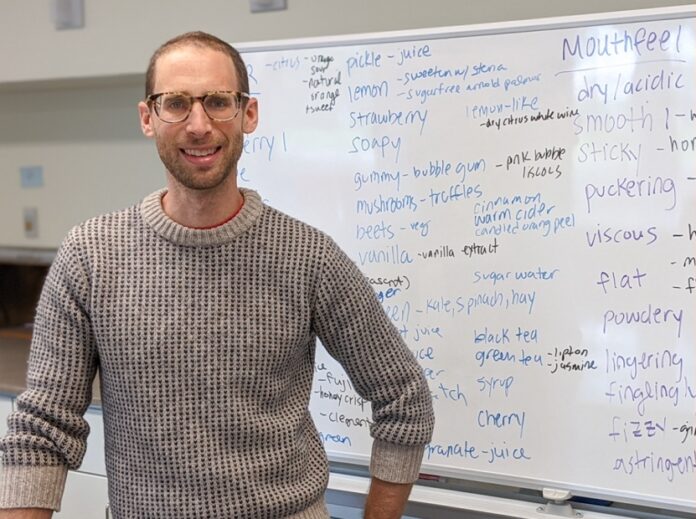

Funded by a $500,000 award from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture, Jacob Lahne, assistant professor of food science at Virginia Tech, and Clinton Neill, assistant professor of population medicine and diagnostic sciences at Cornell, are embarking upon a four-year, multistate research project that aims to create a common descriptive sensory language to help American cider producers communicate their products to consumers.

“The average consumer knows that an IPA and a lager taste different, and they know what to expect if they order one or the other,” Lahne explained. “But that doesn’t exist for cider.”

According to Neill, there’s a reason for that, and it’s exactly what they’re hoping to solve.

“Cider makers have differing opinions about what makes a cider dry or sweet, and this confuses customers,” he said. “If we can aid the cider industry in creating a consistent and descriptive marketing language, then consumers are much more likely to not only try new ciders, but also find a type of cider they can enjoy again and again.”

The duo received funding as part of the USDA Agriculture and Food Research Initiative’s Foundational and Applied Science Program, which provides grants to support research aimed at solving existing and future societal challenges related to food and agriculture. The recent slump of the cider industry presents a particular problem for major apple producing states.

“We had cider makers from all three states we’re working in write letters of support for us,” Lahne said. “Apples are a super important American specialty crop, and they’re a very important specialty crop for Virginia. Cider is a huge value-add that helps support apple growers at a bunch of different scales.”

The first year of the project will see the duo gathering data with a two-pronged approach. To establish a qualitative flavor profile, the researchers will conduct focus groups with both consumers and cider makers in Virginia, New York, and Vermont — three of the largest cider-producing areas on the East Coast and the states the study will focus on — to determine what each group values and looks for when choosing their ideal delicious fermented apple beverage.

Lahne will also use Virginia Tech’s Sensory Evaluation Laboratory to conduct a descriptive analysis, a process in which volunteers will smell and taste an assortment of cider samples and then establish agreed upon descriptor words for each one. This process helps standardize the normally very subjective experience of tasting something new. If a large group of panelists all agree that a certain cider tastes “dry” or “earthy,” it can help remove a lot of the guesswork for producers who want to make a similar cider in the future but aren’t sure how consumers will perceive it. This data will form the researchers’ quantitative sensory profile.

With their sensory lexicon established, the team will conduct a series of tests and surveys to determine if their newfound sensory terminology affects consumers’ enjoyment of cider and how it might alter their purchasing behavior. Neill will then analyze the resulting data and develop it into a marketing language, which the pair will use to create state-specific toolsets to give cider producers and apple growers a clear path to customer preference.

Lahne was adamant that the team does not want to tell cider makers what to make — they just want to give them a better understanding of the people who buy their products.

“We’re not trying to dictate styles to the industry,” he said. “But we are trying to get a big, accurate snapshot of a large sample of ciders so the industry can start rearticulating their sensory qualities for consumers the same way the beer and wine industry does.”

The team plans to have the project completed by late 2024. As of now, their timeline hasn’t been massively impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. According to Neill, the results of their research may be critical to a large number of cider producers, who probably aren’t as big as most people would think.

“Most hard cider producers are small- and medium-sized apple growers,” he said. “By boosting consumption of hard cider, these producers can increase their profits and have a more sustainable business. Apple orchards are not cheap investments and helping them increase revenues and profits is a major goal.”

Lahne hopes they will confirm a long-held hypothesis that might make your local cidery a lot more unique than you probably thought.

“Our theory is that you can make cider that tastes different when you make it from apples grown in a particular place,” he said. “Wine consumers understand that a pinot noir tastes different from a cabernet sauvignon, and also that a cabernet sauvignon made in California tastes different from one made in Bordeaux. But nobody has checked to see if that actually happens for cider, so I’m excited to take a look.”

– Alex Hood