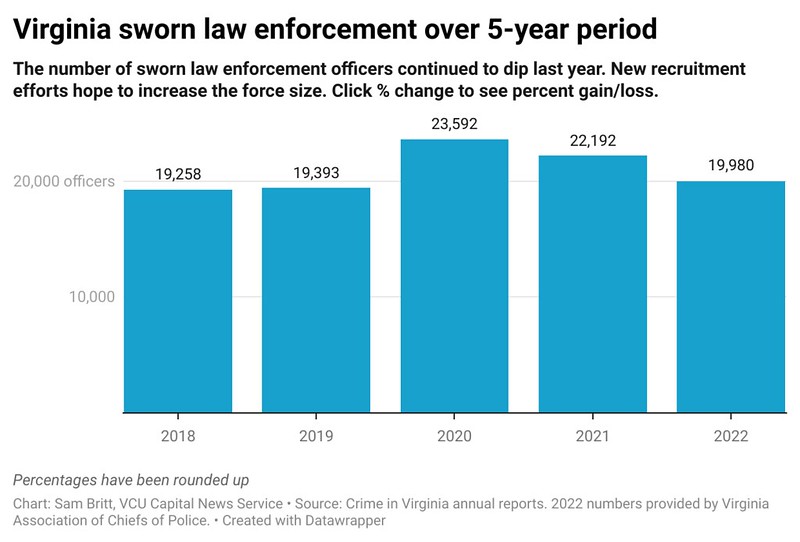

Virginia law enforcement agencies have started to revamp and boost recruitment efforts after a two-year dip in applications. Police hiring trended up from 2018-2020, and then dropped. There was a 21.7% bump in the number of sworn police officers in 2020, from the year before.

However, the number of sworn police officers last year dropped by almost 16% when compared to the number of sworn officers employed in 2020.

The 2018-2021 employment numbers are based on annual reports from the Virginia State Police. The Virginia Association of Chiefs of Police provided the 2022 numbers, since the VSP report has not yet been released. The numbers represent the best approximation of employment that Capital News Service (CNS) was able to obtain.

The number of sworn officers employed last year was slightly higher than the two years before the pandemic, despite the significant dip. There was an almost 4% increase in the number of employed sworn officers last year if compared to 2018 staffing numbers.

CNS asked Dana Schrad, executive director at Virginia Association of Chiefs of Police, if there was any significant recruiting effort or budget funding to explain why 2020 force numbers were higher. She did not reply to multiple requests for that information by publication time.

The loss has been visible in police departments in larger cities such as Arlington, Richmond and Virginia Beach. Arlington has 35 fewer officers than in 2019, Richmond has 137 fewer officers and Virginia Beach has 70 fewer officers, according to records requests from the three departments.

Virginia State Police employment also dipped in a two-year period. VSP has lost 53 sworn officers since 2020, according to annual reports and current information provided by Corinne Geller, VSP public relations manager.

Contributing Causes

Contributing Causes

The number of police officer applications has dropped, but so has the number of qualified candidates, Schrad said. Applications for police chief positions have also decreased, she said.

Law enforcement competes with the private security sector for applicants. And the incoming generation of potential candidates don’t necessarily align with traditional job expectations and demands, Schrad said.

“We see people gravitating, especially the younger generation, gravitating toward teleworking jobs, which of course are not viable in the law enforcement profession,” Schrad said.

Other expectations from an incoming generation include job satisfaction standards that can be harder to meet, according to Schrad. Applicants are not interested in “a ton of overtime.” They expect to rise quickly through the ranks and expect a faster promotion timeline, which is “not the tradition in law enforcement,” Schrad said.

Recruitment videos portrayed the job as a “high excitement” type of profession, but now recruiters are looking for a “different type of skill set,” Schrad said. Other aspects that come with the turf include work on the weekends, in bad weather conditions and exposure to traumatic scenes, Schrad said.

“So the profession is changing, the expectations of applicants are changing and the applicant pool has dropped significantly because of other opportunities,” she said.

The application pool used to be “pretty rich.” “We used to be able to get people despite all the rigors of the job because they felt like it was a profession to be proud of and it was a profession supported by the general public,” Schrad said.

Law enforcement is actively working to change how they showcase the job, recruit talent and “meet the needs of our next generation of potential employees,” according to Schrad.

Recruitment Efforts

Recruitment Efforts

More police departments have reevaluated recruitment efforts. Police chiefs attend job fairs, go to universities, step up their online presence and visit local events to connect with the public, according to Schrad. Law enforcement visits to college campuses and high school classes make potential recruits more aware of agency jobs, according to Schrad.

“They are trying to emphasize the fact that we need officers with good communications skills, with good negotiation skills, that are problem solvers, that are creative thinkers and have a real empathy and understanding of the diverse aspects of our society and the people that they serve,” Schrad said.

Traditional incentives to join include a recruitment package if basic training has been completed, perks like taking the company car home and efforts to purchase newer vehicles and better equipment.

Nontraditional methods include a $15,000 hiring incentive offered by Fairfax County Police for a brief time. The Norfolk Police Department offered a meet-and-greet photo opportunity with two of its “hot cops.” The Norfolk department also used an out-of-state recruitment strategy that included running billboards in the New York City subway, according to WVEC news.

Ride-Alongs

Ride-Alongs

Henrico County Police Department, and other departments, have used ride-alongs as a way to show potential officers what a shift entails. A civilian signs a waiver and rides along with an officer as they cover the local beat.

A Capital News Service reporter accompanied Henrico County police Lt. Jermaine Alley on a busy weekend shift from 7 p.m. to 5 a.m. to learn more about the job and recruitment efforts. Alley is a police recruiter who has been with the force for almost 30 years.

The ride-along allows applicants to see the chain of command, interact with the community and how officers can band together, according to Alley. A majority of the job is as seen on TV: traffic violations and crashes, disorderly conduct calls and service requests, Alley said.

Ride-alongs allow citizens and potential recruits to see how far communication and “negotiating the problems” can go. Alley is able to better understand the candidates, he said. “We need to establish real relationships with them first, instead of treating them specifically like a number,” Alley said.

The tactic also helps a candidate understand how police can work with the community. “The circumstances that I grew up in mirrored the circumstances that I worked in as an officer,” Alley said. “Having those experiences beforehand, positive and negative with police, guided my decision making. I had no problem being a servant to that community.”

‘It’s far worse now’

‘It’s far worse now’

Retired police Capt. Steve Neal, and the author of Toxic Boss Blues, worked for the Chesterfield County Police Department for almost 30 years.

He remembers the time he responded to a scene where an 8-year-old boy was being physically and sexually abused. The case went to court. The boy saw Neal outside of the courthouse, ran to him and hugged him, Neal said.

“It was like being his hero, I saved his life,” Neal said.

Civilians join the force for reasons such as those calls for help, according to Neal. “That is the real benefit of being in law enforcement,” Neal added. “You get to do a lot of good, you make a lot of impact on your community and you even get to save lives.”

Recruitment was always challenging for various reasons, according to Neal. “But it’s never been anything like it’s been in the last couple of years,” Neal said. “It’s far worse now.” He compared public opinion of law enforcement to a pendulum that swings, over the decades, based on political and social ideologies.

The public view of police conduct overall rebounded slightly since 2020, according to a recent Pew Research Center survey. There were sharp racial and partisan divides in the responses. The survey also noted that it was conducted right before the video release of Memphis police officers beating citizen Tyre Nichols, whose autopsy later found that he died from blunt force injuries to the head.

Hundreds of applicants would compete for open jobs in the ‘80s, according to Neal. But now the applicant pool has shrunk, he said. “It is a very different world than it was back then,” Neal said. “It’s just not the same level of interest.”

One policy change Neal thinks could impact recruitment and employment, is to soften some drug policies. Some departments have graduated levels of acceptable drug use. In previous times, if a candidate admitted to any prior drug use, even if it was just once, they were not hired, according to Neal.

“If you smoked a joint … they wouldn’t consider you, you were out,” Neal said.

An Unexpected Career

Danielle Foley is a Henrico County police officer who graduated from the academy in January 2020, right ahead of what became a tumultuous year. She was recruited to Henrico police by Lt. Alley.

Although she was still fairly new to the force, everyone said they were working in “completely uncharted territory,” Foley said. The year 2020 brought police officers on the same platoon together even more, and led Foley to some of her closest friends, she said.

Foley graduated from Virginia Commonwealth University with a double major in criminal justice and psychology. Most police departments only require a high school diploma. A college degree can give an officer the advantage to learn more about law enforcement, and also the criminal justice system as a whole, according to Foley.

Foley was drawn to the public service part of the job, she said. “We don’t typically interact with people on the best day of their life,” Foley said. “Usually it is one of the worst days of their life, or they are really going through something ‒ and that’s why we’re there, so we can help them in whatever way that we can.”

The decline in police officers has impacted how they respond to calls. Dispatch has to “triage” and prioritize urgent calls. The motto is just take it “a call at a time,” according to Foley. “You give each call still the attention … that it deserves and … just figure out a way to get to everything that we need to get to,” Foley said.

Looking to The Future

Looking to The Future

There needs to be more recruiting of people of color and women to better diversify the police force, Schrad said. Women accounted for 20% of sworn officers in 2021, based on the most recent VSP report that included gender.

“We’re hoping that the image of law enforcement will start changing,” Schrad said. The force might be very different in 10 years, according to Foley and other officers interviewed.

“Our world and our society is ever changing, our profession will just have to continue to change and grow,” Foley said. “We will certainly need to, whether that’s you know, look at policies and procedures or if it’s just changing the way … we interact with people.”

“We just need to be ready for whatever’s coming down the pike,” Foley added.

By Samuel Britt / Capital News Service