Two non-profit organizations dedicated to preserving and sharing often-overlooked chapters of history, the West Virginia Mine Wars Museum and the Chesapeake & Ohio Historical Society, have partnered to commemorate the 150th anniversary of the first coal shipment from the New River Gorge in 1873. While coal mining was already established in West Virginia prior to the opening of the New River Fields, the first loads transported from the remote New River Gorge represented an industrial conquest of nature years in the making.

From the time the Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad was incorporated in 1869, Collis P. Huntington, the corporation’s leader for whom the city of Huntington, West Virginia would later be named, sought to connect the east coast with western destinations with what had long been called the “Great Connection.”

On a cold spring day in 1870, the English-born John Nuttall, who possessed a deep coal-mining background from his native country, reportedly entered the Alderson Tavern near Winona while traveling west through Fayette County to assess the seams of the Kanawha coalfields. While stopped, not only did Nuttall notice the tavern fire was burning coal instead of wood, as was the case on other layovers along the James River and Kanawha Turnpike, but he recognized the coal to be of incredibly high grade.

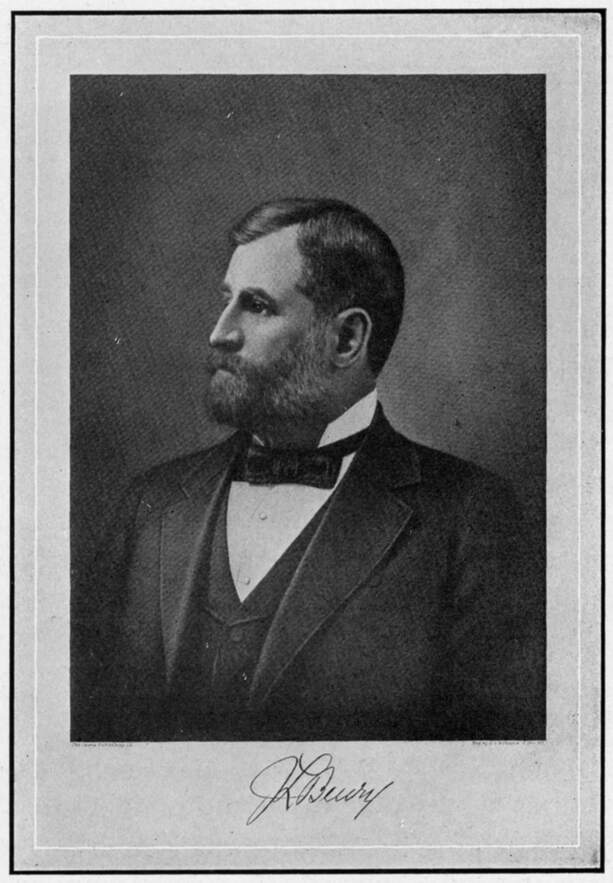

Asking the proprietor, Mr. Alderson, where he had found his brightly-burning coal, Nuttall was later taken by his host down Keeney’s Creek with its outcroppings of coal from the Sewell seam. The 53-year-old Nuttall, for whom the town of Nuttallburg would later be named, realized there was a fortune waiting in the Fayette County hills. But until the railroad was completed from the Virginia coast to the Ohio River in January 1873, driving the C&O’s main line through the New River Gorge for access to the nearly untapped coal seams, there was not a method to cost-effectively export coal from the region, one of the most rugged in the eastern United States. With the C&O Railroad completed through the West Virginia terrain, in September mine owner Joseph Lawton Beury began exporting coal by rail from his mine located near present-day Quinnimont.

Nuttall would also operate several coal mines until his death in 1897, with his town of Nuttallburg expanding in population and profitability. The Chesapeake & Ohio Railway (as it was called after 1896) would become a predecessor company to CSX Transportation, now a Class I freight railroad operating in the eastern U.S. and parts of Canada.

The first industrialist to export coal from this region of West Virginia, writing the first page of coal mining history in the New River Gorge that would span over 100 years, brought with him to the state his own colorful history. Born August 15, 1842 in Schuykill County, Pennsylvania, Joseph Lawton Beury had been a captain in the Union army during the Civil War and had gained coal mining expertise from his father’s anthracite mines in his home state. With knowledge that the C&O Railroad was building its way toward the New River Gorge, he and his wife moved to West Virginia and established the town of Quinnimont. Ready to ship coal once the railway was completed, it was from this location that the first carload of soonto-be coveted “New River Smokeless Coal” rolled into history.

Beury went on to expand his coal operation into an empire, leaving Quinnimont in 1876 to open mines at nearby Fire Creek, and later at Hawks Nest and Ansted. By 1884, he was an owner in the first mine on the Flat Top area of the Pocahontas Coalfield. One of the major coal operators in the state, Beury built a twenty-three-room mansion in the New River Gorge, in a town near Thurmond that bore his name.

West Virginia Mine Wars Museum Education Coordinator Lloyd Tomlinson describes the population growth that followed Beury’s history-making export, “As the New River Coalfield grew, so did its population. The men and boys who worked in the mines, as well as the women and girls who lived with them in the company towns, came from diverse backgrounds. In addition to American-born whites, African Americans and European immigrants made up significant proportions of the workforce. This trend played out throughout West Virginia as the coal industry grew to accommodate the United States’s industrial needs.”

Barbara Beury McCallum of Charleston, West Virginia, great granddaughter of “Colonel” Joseph Lawton Beury, remembers family stories and moments from her own upbringing that reflect life within the coal empire that started with that first carload shipped from Quinnimont within the New River Gorge 150 years ago. Her late sister Elizabeth was caretaker of many family photographs, such as her Aunt Daisy’s wedding pictures at the town of Beury showing the interior of the family mansion, the wedding ceremony, and many extravagant gifts. McCallum said a special Chesapeake & Ohio Railway train was hired to run from Charleston to the Fayette County mining town carrying wedding guests for Joseph Beury’s only daughter.

According to McCallum, the C&O Railway would stop a passenger train at Beury for her grandfather when he needed to travel, even though the town was not an official stop on the railroad at the time. Later her father, the last son to live in the town of Beury, was a railroad buff and went across the United States several times by rail. As a child, her father could remember when the only way into Beury was by train.

In those years, he went to the tracks and retrieved the newspaper from Charleston off a railroad mail hook so he could read the funny pages.

As children, great granddaughters Elizabeth and Barbara were trained, when they spotted a C&O Railway diesel locomotive, to say, “dirty diesel, dirty diesel,” because those later-era locomotives were not coal burners as earlier steam-powered locomotives had been.

Tomlinson points out that the coalfields in this region of the state grew to intersect with the bigger picture of West Virginia labor history, “The New River Valley was also the site of an important precursor to the West Virginia Mine Wars. In 1902, ten thousand miners walked off the job, shutting down eighty percent of coal production in Fayette County. The striking miners and their families endured conditions that became defining elements of the Mine Wars: tent colonies, blacklisting, and the brutality of Baldwin-Felts mercenaries and county deputies paid for by the coal operators. The 1902 strike set the stage for later labor conflicts in southern West Virginia, culminating in the Battle of Blair Mountain.”

Barbara Beury McCallum pointed out that, unlike most coal barons of the time, her great grandfather was not an absentee owner. Seeing a need in his community following the West Virginia Legislature’s 1899 creation of three miners’ hospitals, Joseph Beury donated land at McKendree, West Virginia, near his mine at Quinnimont, for construction. Opening December 1, 1901, Beury supplied heating coal at no cost to Miners Hospital No. 2 for several years. Also known as McKendree Hospital, the facility also treated injured workers and residents from the region, eventually expanding to a campus that included a 17-room nurses’ home building with a tennis court. Countless nurses would be trained at Miners Hospital No. 2 in exchange for a two-year commitment to stay at McKendree.

Joseph Lawton Beury died June 3, 1903, in the West Virginia town that bore his name. In the 1920s, fellow mine owners of Beury’s erected a twenty-five-foot tall, fifty-five-ton granite monument at Quinnimont that still stands today overlooking the place where the first railcar of coal was exported from the New River Gorge. Its inscription reads, “The first New River smokeless coal was mined and shipped from Fire Creek Seam at Quinnimont by Joseph Lawton Beury in 1873. This memorial erected by his coal associates in the New River District.”

In 2023, the C&O Historical Society commemorated the sesquicentennial of the railroad’s completion in the New River Gorge that fulfilled the nation’s long-desired “Great Connection” between east and west. Though Collis P. Huntington would only control the company for a short period of its total history, losing control 15 years after the main line was completed in 1873, the railroad set the stage for generations of economic development. Totten notes, “With its throughfare that passed through the New River Gorge, the C&O Railway changed West Virginia history forever. Not only did rail access enable industrialists like Joseph Beury and John Nuttall to develop the region, but behind their groundbreaking efforts, thousands of West Virginia workers and their families settled into newly-built towns within the wilderness, added volumes to our history books, and made a permanent imprint on how we define West Virginia culture.”

West Virginia Mine Wars Museum Education Coordinator Lloyd Tomlinson concludes, “We at the West Virginia Mine Wars Museum hope that this commemoration can help to forge a relationship between our two museums and tell a bigger story about West Virginian, Appalachian, and American history.”

On the sesquicentennial of her great grandfather’s legacy, Barbara Beury McCallum reflects, “I’m glad he is still being honored today. He was one of the few coal operators who didn’t live out of state and put his money back into West Virginia. He had a community here and was an honorable man. I’m just glad he’s still being recognized today for the things that he did to develop the coal industry in West Virginia.”

Barbara Beury McCallum is helping bring her great grandfather’s legacy of reinvestment in West Virginia full circle. Following Elizabeth Beury’s passing in January, she is in the process of setting up a fund with The Greater Kanawha Valley Foundation for both university and vocational scholarships. Through the future award of that money to local students, that educational legacy has a deep meaning to McCallum, symbolizing that her great grandfather was still giving back to the state of West Virginia, stating, “In that way, people are still benefiting from what Joseph Beury did.”

C&O Historical Society President Mark Totten concludes, “One hundred and fifty years after ‘Colonel’ Beury and his workers shipped the first railcar of coal from the New River Gorge, the same region in Fayette County is still vital to our state’s economic future, and the former Chesapeake & Ohio Railway main line is still an important part of CSX Transportation’s rail network, shipping coal and other freight daily between east and west. That’s a legacy that should not be forgotten.”

The West Virginia Mine Wars Museum is open Wednesday through Saturday from 10 AM – 5 PM at 401 Mate Street, Matewan, WV 25678 and may be contacted by telephone at 304-691-0014 or by email at [email protected]. For decades after the 1921 Battle of Blair Mountain, the stories of the Mine Wars were whispered around kitchen tables and bullied out of textbooks, surviving as a quiet legacy just under the surface of modern Appalachia. The West Virginia Mine Wars Museum preserves and uplifts the voices of the people who lived these stories of sacrifice, violence, and triumph. Updates and additional information can be found on Facebook under @WVMineWarsMuseum.

The C&O Historical Society’s Business Office & Archive may be contacted by telephone at 540-862-2210, Monday-Friday, 9 AM – 5 PM, or by email at [email protected]. The C&OHS archive database is available online at archives.cohs.org. Updates and additional information can be found on Facebook under @cohs.org or on Instagram @ChessiesRoad.