Herein lies a serendipitous reprise of an article I stumbled across this morning—exactly three years from its publication on Sustain Floyd’s website (from which I copied and pasted.) I’ll say more about its origins and use in the endnotes, for both of you troopers who persevere to the end.

It is told that, in the forests of post-revolutionary Virginia, the widely-spaced mature trees stood so tall and created so much shade that a gentleman could ride horseback from Richmond to Bristol and never take his hat off to brush and low branches. A squirrel could cover the same distance without touching the ground.

But it didn’t take many generations for a burgeoning nation to see the utility of trees for framing, furniture and fiber, and forests as an impediment to the spread of suburbs and cities, roads and railroads, shopping malls and golf courses.

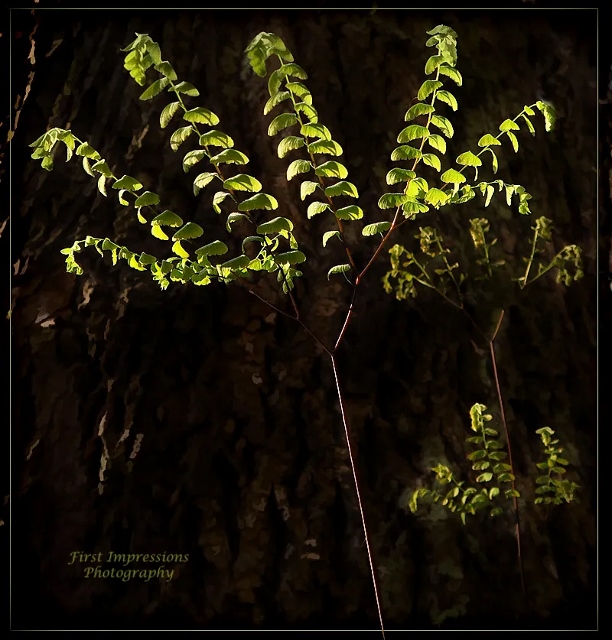

Even so, from the orbiting Space Station, while some mountaintops are missing now, the landforms from the Virginia Piedmont to the Appalachian Plateau are little changed since Plymouth Rock. Here at ground level, we still live in a sea of trees (as you can see on the approach to airports in Roanoke or Bristol). But the forest is not your father’s forest; and she is no virgin.

While the sheer number of trees in the East is, in fact, increasing (as the center of agriculture has moved west), tree size, and–especially in pine

plantations–forest-community diversity has declined. Individual trees in fields or forests or in cities or suburbs rarely survive to their potential size anymore. But a few do. And in discovering and celebrating them is hope–that we are paying attention to these exemplary trees and perhaps someday soon, to a future that includes more eastern old-growth forests.

So as you travel the 330 miles of the Crooked Road across the southern, then far western tier of counties, Rocky Mount to the Breaks Park, be mindful that, while the woods out your window may only seem impressive in sheer numbers, there are record-making Old Trees somewhere in a holler just over the ridge. (BIG is a factor of height, trunk circumference, and crown spread within members of a species.) The Virginia Big Tree Program coordinated by Virginia Tech maintains a database so that you can learn about, possibly visit, and add your own record-sized trees.

Before you begin your perusal of Southwest Virginia’s big tree web resource, a few user tips: Unless you select “Common Native State Champions” you’ll see in the list many tree species that, even if you’re a competent forester, you won’t know because they are “not from ’round here.” They are non-native intentionally-planted ornamental or otherwise attractive or desirable for city life, but are not part of the tree mix the First Americans lived among.

Also, for many of the native-species record holders in the Big Tree registry, you will find that they are disproportionately found in big cities, not in the remote woods of more sparsely-settled places like Crooked Road counties. This makes sense. There are way more “finders” in Richmond than Richlands; and life is tree-easy in a dog park where sycamore or birch stand widely spaced and don’t compete for light, water or soil nutrients. But a tree’s life can be harsh and growth slow on a windswept ridge or in a cold, north-facing cove in Damascus / Washington County.

In Southwest Virginia, record Big Trees are almost all on private property. But you can find more than 250 in one spot, some of them estimated to be more than 400 years old. Virginia Tech’s Stadium Woods in 2012 almost became a construction site. Wide support for preservation has at least temporarily protected this remarkable 11 acres on campus as an irreplaceable resource. Now this was the kind of woodlands our gentleman on horseback would have happily galloped through so long ago.

We admire and honor big trees. We might even a hug a few. But we need forests on these steep slopes–intact, diverse, soil-making, water-storing, oxygen-emitting, carbon-holding forests. The diversity of North American life arose in ancient forest ecosystems and is rapidly disappearing from them now as few woodlots even reach middle-age. Old Trees are wonderful specimens, but Old Growth forests will be an intentional choice we make on our public and private lands in these pleasant mountains.

We admire and honor big trees. We might even a hug a few. But we need forests on these steep slopes–intact, diverse, soil-making, water-storing, oxygen-emitting, carbon-holding forests. The diversity of North American life arose in ancient forest ecosystems and is rapidly disappearing from them now as few woodlots even reach middle-age. Old Trees are wonderful specimens, but Old Growth forests will be an intentional choice we make on our public and private lands in these pleasant mountains.

Come for the music, but don’t miss the forest for the trees. Find more about Virginia’s Big Trees at http://bigtree.cnre.vt.edu/index.html.

ENDNOTES:

I was invited a few years back to contribute an essay, topic of my choice, to the Mountains of Music celebration—part of the Round the Mountain Artisan Network. The topic of Old Forest later lead me to the opportunity to engage Dr. Eric Wiseman of Virginia Tech in a discussion about the Old Trees Registry in the Commonwealth.

You can see the zoom interview with Dr. Wiseman. This focus on big trees and forests was one small part of the Blue Ridge EcoFair in 2020. This was SustainFloyd’s VIRTUAL project during the Covid Years, following two previous years of successfully building interest and regional participation.

Fred First is a life-long biology-watcher and naturalist, sharing his view of the world from a remote valley in northeastern Floyd County. From here, his blog, his books and his radio essays have taken root. He has been an active teacher and community participant in SWVA since 1975, sharing his hope that we might see the ordinary and our place in and impact on the world around us with new eyes–a knowledge of belonging that he advocates and calls our “personal ecology.”

Thanks for joining me. Subscribe to My Substack HERE