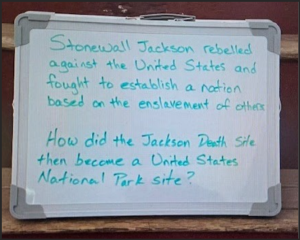

In early August, the Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park (FSNMP) placed a hand-lettered sign inside of the Stonewall Jackson Death Site. Known to many people as the Jackson Shrine, it’s a plantation office building where Jackson was brought after being wounded at the Battle of Chancellorsville. Jackson died there; hence the site’s name.

The sign said this: “Stonewall Jackson led an army that fought against the United States with keeping slavery as one of their goals. Why then did this place become a United States National Park Site?” FSNMP says this sign is part of an initiative to “spark conversations and to broaden the story of the site and context for Jackson’s death and memory.”

If the first things that come to the National Park Service’s mind, when it thinks of the most noteworthy aspects of Stonewall Jackson’s legacy, are that he fought for the Confederacy and the Confederacy supported slavery… then we really do need to have a conversation.

No mention either of the Sunday School Jackson established for local slaves, funded and operated in Lexington. Many whites, remembering Nat Turner’s slave rebellion, feared slaves being taught to read. Jackson was not swayed. When several prominent Lexingtonians threatened him with legal action if he didn’t close the school, Jackson refused.

Jackson had every reason to fear that he could lose his job, he and his family could be ostracized, and a brick might fly through his window (or worse). Yet, he operated the school until he died. In comparison, nowadays some people curl up in the fetal position if they get a couple of nasty Tweets.

Stonewall Jackson deserves to be remembered as a bona fide American hero, one of the best our country has produced. Did he have flaws? Yes! Many of them, in fact. David McCullough, one of America’s great popular historians, in the epic “The Civil War” PBS miniseries called Jackson “an eccentric student of theology and military tactics [and] a hypochondriac.” And McCullough wasn’t exaggerating.

But Jackson’s accomplishments WERE great. In 1862 and 1863 he was the dominant field general, Union or Confederate, in the Civil War’s eastern theater. “Jackson’s strategic innovations shattered the conventional wisdom of how war was waged,” says the cover of Rebel Yell, a 2014 biography of Jackson by S.C. Gwynne, a journalist and Pulitzer Prize finalist.

“[H]e was so far ahead of his time that his techniques could be studied generations in the future.” But he was more than just a great general…he was a great citizen, too, as his Sunday School for slaves attests.

Stonewall Jackson was an imperfect man who was a product of the times he lived in. We do not think and believe now the way that people thought and believed then. “The past is a different country,” said British author L.P. Hartley. “They do things differently there.” If we judge Stonewall Jackson’s legacy fairly, we will see that his accomplishments, courage and character outweigh his personal flaws and the many flaws of Southern society in the mid-1800s – and ALL the societies before it that slowly found their way to a slave-free economy.