When the History Channel needed an expert to help weigh in on the theory that John Wilkes Booth may have survived beyond 1865, they called on the expertise of Virginia Tech computer science associate professor Kurt Luther.

Luther and his Civil War Photo Sleuth software were featured on the History Channel’s The Escape of John Wilkes Booth last weekend as part of its “History’s Greatest Mysteries” series.

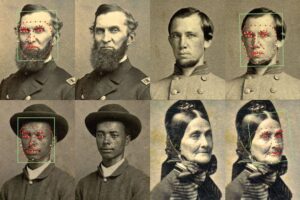

Since the episode aired on Saturday, Luther said he has seen noticeable traffic, users, and uploads to the Civil War Photo Sleuth website. Powered by a database of more than 30,000 images, it brings together the complementary strengths of both human intelligence and artificial intelligence (AI) using facial recognition.

Twelve days after the assassination of President Lincoln, history records show that Booth suffered a fatal gunshot wound while resisting arrest. Today, the Booth family believes he faked his death, reunited with his wife, going on to marry again under an assumed name, eventually revealing his true identity in a series of clues.

Through the Civil War Photo Sleuth Facebook page, the History Channel show’s producers contacted Luther as they had been granted access to 60 boxes of rare documents at Harvard University that could speak to the mystery.

The producers were specifically interested in the photo sleuth’s cutting-edge facial recognition technology to see if they could make any positive photo identifications to Booth. Since its launch in 2018, users have uploaded photos, tagged them with visual cues, and connected them to profiles of Civil War soldiers with detailed records of military history to the photo sleuth website.

These visual clues, such as coat color, chevrons, shoulder straps, collar insignia, and hat insignia, are then linked to search filters to prioritize the most likely matches.

The site then uses the facial recognition AI to further cluster photos based on their similarity. Both steps help “narrow the haystack” for the user that comes onto the site to search for a specific soldier. That’s where human intelligence comes in: users find the needle in the haystack by exploring the highest-probability matches in more detail, and deciding on them.

The History Channel provided Luther with two different photographs of Booth as a “test subject,” said investigator Arthur Roderick, a retired U.S. marshal and law enforcement media consultant, who interviewed Luther at his Virginia Tech office in Arlington, Virginia, in October 2019. The software was able to successfully match the two different Booth photographs among more than 30,000 possibilities.

Moving from the known photos of Booth, the database was put to the test to see if could make any identifications with two other photographs: one of a man named James William Boyd that had strong physical resemblances to Booth, and the other a high-resolution scan of an old tin-type of John St. Helen, an assumed name allegedly used by John Wilkes Booth. Luther found no match with the known photos of Booth in the database, refuting the theory that Booth survived under one of these assumed identities.

Due to COVID-19, the crew had to delay the release of the episode which was originally set for April this year to coincide with Lincoln’s assassination on April 15, 1865.

This is not the first time Luther and his team have been tapped to identify unknown people and places in historical and modern photos, as well as combat misinformation. The Crowd Intelligence Lab, led by Luther, researches the complementary strengths of crowdsourced human intelligence and artificial intelligence in domains like journalism, history, national security, and creativity.

The team consists of Vikram Mohanty, a doctoral computer science student; Paul Quigley, the James I. Robertson Jr. Associate Professor of Civil War Studies in the Department of History at Virginia Tech; and Ronald S. Coddington, editor and publisher of Military Images Magazine. Quigley currently serves as the director for the Virginia Center for Civil War Studies, housed in the Department of History.

Luther also serves as a senior editor for Military Images, a quarterly magazine dedicated solely to the study of portrait photographs of Civil War soldiers, where he writes about his real-life accounts on the research trail.

Most recently, Luther and his team were contacted by Snopes, the fact-checking website, to debunk modern disinformation through Civil War photo databases as it related to the claim that President-Elect Joe Biden’s great-grandfather owned slaves.

The lab serves as a connective hub between several areas across the university, including the Center for Human–Computer Interaction, the Hume Center for National Security and Technology, the Institute for Creativity, Arts, and Technology, the Information, Trust, and Society Initiative, and the Tech for Humanity Initiative.

In addition to his primary appointment in computer science, Luther is a faculty affiliate of the Department of History.

“There is great excitement around artificial and facial recognition as it being used for an increasingly wide range of applications,” said Luther. “The relationship between history and technology can also help us solve mysteries that have existed decades and even centuries.”

— Jenise L. Jacques